The Artists

Humble Beginnings

Early Australian paintings were colonial in nature, depicting the growth of the new society, the native flora and fauna, and the lives of the Aboriginal peoples.

The main obstacles to the development of Australian art were poverty and isolation. No master artist would relocate to an impoverished penal society which could neither pay him nor appreciate him, and the distance involved meant that high-quality paints were not easily imported.

Since there were few professional artists in the early days, many of the early artists were former convicts. Their art was done with pencil or with watercolours made from local ingredients.

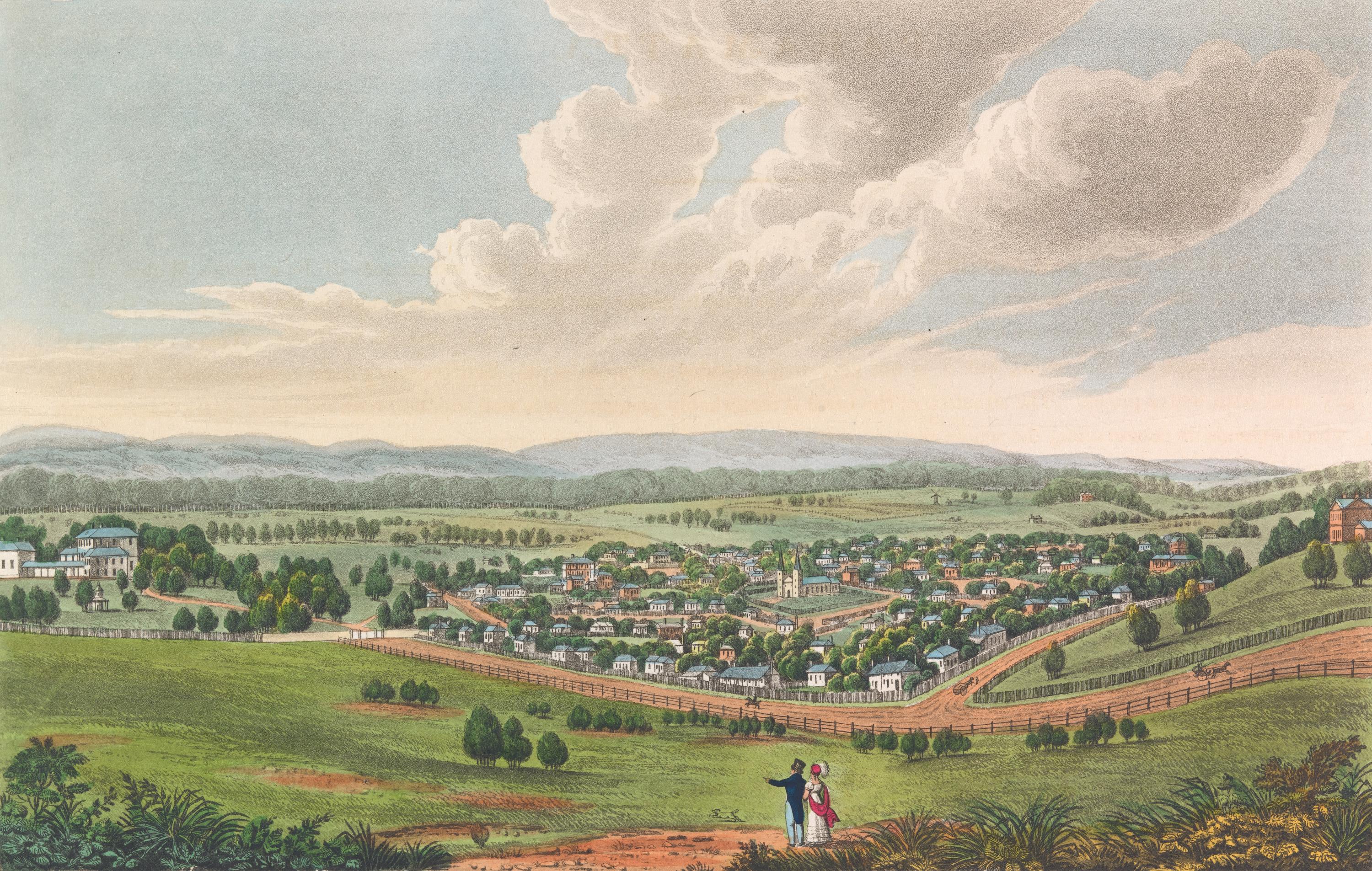

Joseph Lycett was one such artist. He made numerous works showing towns, landscapes, and Aboriginal customs.

In showing early Australian towns, his pictures show both the humble beginnings of Australian society and the humble beginnings of Australian art.

Paramatta is a good example. Two centuries later it is a city of more than 250,000 people, within greater Sydney and its millions, but this painting shows its origins as a well-ordered village with a church at its heart.

Although these early artworks are often well-executed, they are valued more as memories of an earlier time rather than as the masterpieces of a nation.

European Masters: Nicholas Chevalier

By the middle of the 19th Century, Australia had begun to move on from its convict origins and became home to several master artists from Europe.

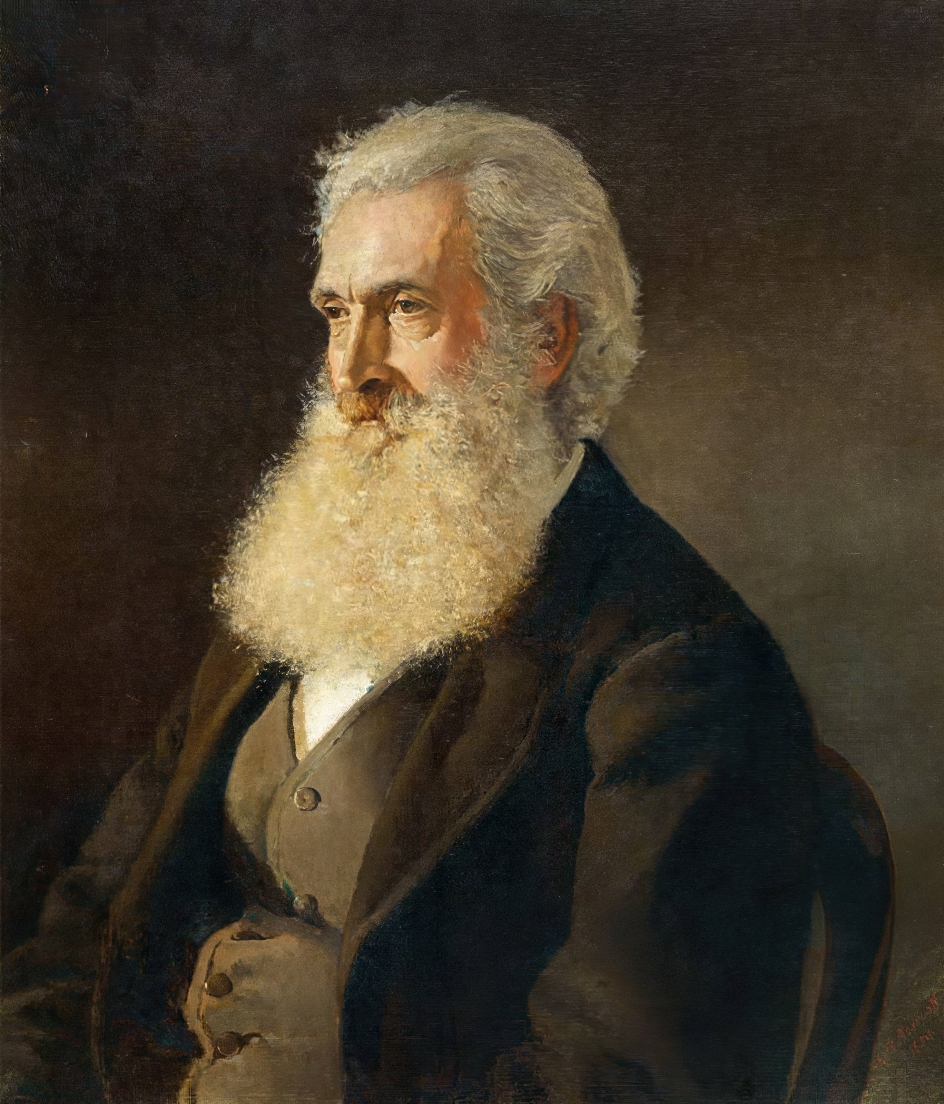

Nicholas Chevalier was one of them. He was born in Russia in 1828 and arrived in Australia in 1854.

Chevalier and his wife were intelligent, witty, and diplomatic. They were at the centre of a circle of artists, writers, and educated men.

His good reputation made the Duke of Edinburgh request his presence for his tour of Tasmania. The Duke liked him well enough to again request his company the following year on a second visit.

Chevalier returned with him to England, where he produced over 100 works for Queen Victoria.

His work, The Buffalo Ranges, was considered one of the first great Australian paintings. It won an award and was one of the first Australian paintings to be displayed at the new National Gallery of Victoria, where it was enormously popular.

Works like this marry the Australian landscape and pioneering activities of its people with a European-style presentation. The water wheel and the nearby rocks, the bullock team in the foreground, and the snow-capped mountains behind a green forest combine to make a dramatic scene.

European Masters: Eugene von Guerard

Eugene von Guerard was born in Austria in 1811 and arrived in Australia late in 1852.

After failing to make his fortune on the goldfields, he decided to put his art training to good use.

He joined the scientific expeditions of Alfred Howitt in 1860 and Georg von Neumayer in 1862. Though it had been 70 years since the arrival of the First Fleet, the area under settlement was tiny and many areas were scarcely recorded.

Capable artists were needed on such expeditions to provide accurate renderings of the landscapes, plants, animals, and Aborigines.

Artists were important parts of such expeditions, for art was seen as a compliment to science.

Estate or homestead painting was another artistic tradition. If a landowner was proud of their homestead and the work they had done, they would paint a record of their accomplishment. If someone had not the talent but had the money, they would hire a professional. Commissions followed Guerard wherever he went.

Estate paintings are an important part of Australia's art heritage because most art was privately held, there being few public art collections at that time.

Yalla y poora shows a fully functioning and wealthy sheep station.

A lake, a bridge, a carriage with departing guests; a row-boat upon the water, flocks of birds and animals, station hands, windmills, fields, and a wool shed in the background beneath the gaze of Mount Challicum, show a homestead full of life and labour.

Yalla y poora was one of the last great estate paintings made by Guerard; they went out of fashion as Australia developed. These works helped him rise to a leadership position in the Australian art community. Several of his paintings were purchased by European royalty.

European Masters: Louis Buvelot

Louis Buvelot was born in Switzerland in 1814 and came to Australia in 1865.

Paintings such as Summer Evening, near Templestowe are characteristic, with a skilled use of light and tone to give a deep sense of realism.

Sheep are being driven up the dusty road by a drover and his dogs; village folk talk outside their houses near a herd of cows; a field in the back has cows eating hay; a tall tree rises in front of the clouds, and the whole scenario is framed by a mound to the left and a hill to the right.

Paintings like this inspired the next generation of artists so much that they named Buvelot the father of Australian landscape painting.

The time of simple but good colonial paintings was well and truly over. Going too was the time when Australia would look to European masters.

Soon Australia would produce artists of its own, and art would no longer be merely in Australia or about Australia, but of Australia and for Australia. The results would be quite literally nation-defining.

The Impressionists

A young Australian artist by the name of Arthur Streeton was so inspired by the work of Louis Buvelot at Templestowe that he went out to make one of his own.

Returning to Melbourne by train with the wet canvas, another passenger liked what he had done and offered him the use of an old abandoned farmyard, which he and a company of others had acquired.

When Streeton arrived at the farm in Heidelberg, he found an 'old ruin, creaking and ghostly, with a long dark corridor that seemed full of past visions.'

There was no furniture, and only an old caretaker at the far end of the house. His first night was spent in solitude upon the floor, sleeping only with the aid of tobacco and wine.

He was soon joined by his friends Tom Roberts and Charles Conder. They were visited on occasion by other artists such as Frederick McCubbin and Walter Withers.

Through all the annals of Australian history, no men can compare in influence to the men of Heidelberg upon the art of Australia.

They were the source of some of the most beloved and iconic pictures of Australian life.

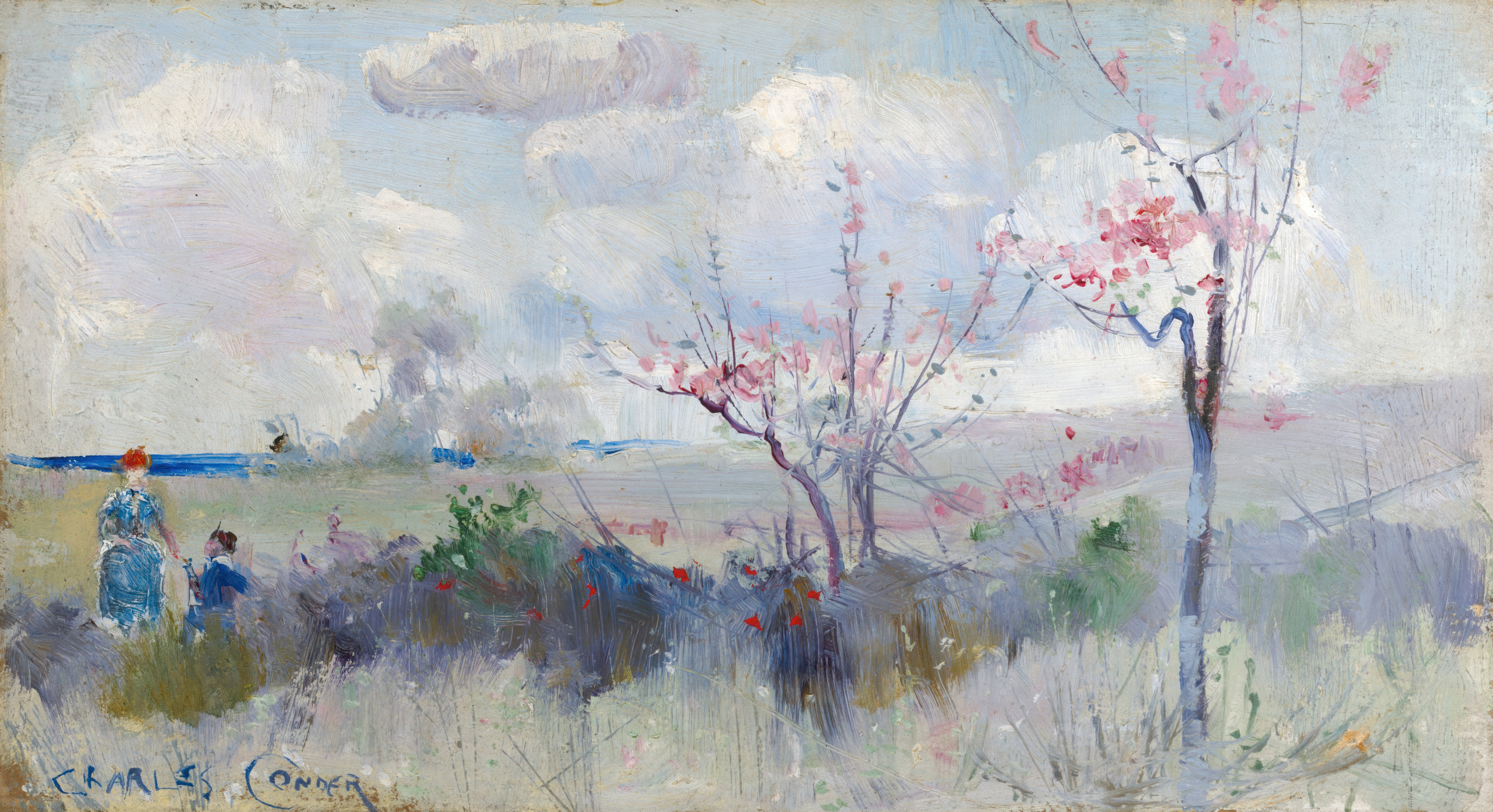

Conder looked back fondly on his time at Heidelberg in a letter to Roberts: "Give me one summer again, with yourself and Streeton: the same long evenings, songs, dirty plates, and last pink skies. But these things don't happen, do they? And what's gone is over."

Streeton would later write: "He [Conder] and Roberts were the most intimate and generous friends I ever had in our labours of last century."

The trio that slept in potato sacks and had to make their own furniture were about to create Australia's very own national art school, one whose works adorn this Australian book more than any other.

The 9 by 5 Exhibition

Tom Roberts had recently returned from a tour of Western Europe where he had come into contact with a new art style known as impressionism, in which the focus was on giving an impression of a single moment.

The artists of Heidelberg understood that this technique was an excellent fit for depicting the Australian life and landscape. The style they painted in came to be known as Australian Impressionism.

They painted a series of small impressions on wooden cigar box lids, a popular substitute for canvas.

Measuring 9 by 5 inches, these were provided for free by friend and art patron Louis Abrahams, whose family owned a cigar import business.

A suitable gallery was found in Melbourne and decorated with silks, drapes, Oriental-style umbrellas, and vases. Charles Conder created an elaborately drawn catalogue for the event.

Everything was carefully planned and organised, but the exhibition was a disaster. The reviews were so bad that the artists took to pasting them up outside the gallery. Passersby stopped and came in to see what all the fuss was about. Suddenly, the exhibition was a huge success.

The paintings that were so derided by professional critics were very popular with the public and nearly half were sold in a few days.

Herrick's Blossoms by Charles Conder, Hoddle Street 10pm by Arthur Streeton, and Going Home by Tom Roberts were some of the favourites of the show.

This is Australia's most famous art exhibition and it launched the career of the men who would become Australia's very own master artists. The Impressionists would never again be short of fame or fortune, and the Australian People would never again look to outsiders to paint the pictures of their world.

Australian Impressionism

When they were not painting small impressions on cigar box lids, the Impressionists used a more refined technique to create large-scale epic works.

Arthur Streeton used this technique to devastating effect in Golden Summer.

The scene was a meadow at a time of drought near Mount Eagle, 'our hill of gold' as he called it. A shepherd boy and his sheep can be seen on gold-coloured hills while a lone magpie sits calmly nearby. A farmhouse and river valley appear in the background.

The work was immediately understood to be a true Australian masterpiece. With its warm, soft light and hazy summer heat, it perfectly captured the Australian landscape as Streeton saw it.

Featuring a people at ease with nature, confident in what they have made, and confident in what they yet will make, images like this were a major part of the strong nationalist sentiment that appeared in the late 19th Century.

In the Open Air

Where artists had traditionally drawn sketches outside before retreating to the studio to paint the final image, advances in technology had made easels and paints more portable, and for the first time the artist became as free to paint outdoors as he was within doors.

This was known as en plein air, which is French for 'in the open air'. Artists and their camps became a common sight outside the cities. The best locations were those that gave good views of nature for painting and good access to the cities for supplies.

After their time at Heidelberg had ended, Streeton wrote to Roberts of his desire to go away from society.

He wanted to "translate some of the great hidden poetry that I know is here, but have not seen or felt it."

He ascended to an escarpment above the Hawkesbury River, looking toward the Blue Mountains. Over the course of two days, in temperatures over 40 degrees Celsius, he painted in an 'artistic intoxication', stopping only to meditate and read poetry. The result was The Purple Noon's Transparent Might.

One reviewer wrote: "No one can paint distance like him. Every touch here is sure and relevant of character…

"Who but Streeton, gazing up the Hawkesbury River from the terrace across those far-stretched plains, could have imagined what he saw?

"To divine the possibilities of a picture, its shapes and lighting, its character and composition in that wide field, required the intuition of genius. It was virgin landscape, untouched of any brush.

"He possessed no formula, no precedent to rest upon – only his vision; but that, developed by continuous painting in the open, was ready to resolve its difficulties. When he had finished it, I doubt whether Streeton was aware of the importance of his accomplishment."

Australian Art

It was in the field of art that Australian culture reached its perfection.

In little more than a century, Australia had developed its own artistic heritage. It began with simple colonial art, when the world of Australia was young, and advanced with the work of European masters. Finally, it completed its ascension with its own masters who worked with nationalism and sentiment.

Sunday in the Sydney Art Gallery by Julian Ashton shows how far Australia had come in so short a time. This black and white drawing from 1889 is of limited value artistically, but is noteworthy historically.

In it are rows of paintings being admired by a crowd. Yet a generation earlier, there had been no public art galleries in Australia. Most works in the gallery would have been imports but an ever increasing number were Australian. These were some of the more popular works, and their creators became household names.

This shift was helped along by Ashton himself, who was a great believer in Australian art and a veteran of the industry who taught and encouraged many.

Now that the men have gone and all memory of them has faded, the paintings of the age remain to give us a portrait of the soul of their world.